The figures of the Italian folklore are no way inferior to those in Ireland, both in number and variety; even in Lombardia we have a fair amount of such. If is true that elves and goblins are scarce, although not entirely absent (it seems to exist only one of these, known as “Piripicchio”, that is the principal of a legend set in Albosaggia, in the province of Sondrio), however we find in abundance chimerical beasts, ghosts, various devils and witches.

Let us start this review with the Bargniff: it is a mythical being who lives under the bridges crossing the muddy waters of the rivers Po and Ticino, notably between Milano and Pavia. Usually is described -by those who had the misfortune to spot it- as a flaming-eyed, huge toad or ox. The “Bargniff” has definitely devilish nature and the wise man should avoid it at large. It is better not to wander along marshes and waterways overnight: you could meet it and it could then cast one of its almost insoluble riddles. Most likely you would be unable to solve it, and so the “Bargniff” will jump on you and drag you into the icy water until you are drowned, while he mockingly laughs with fury. Trace the origins of this myth, as all the other ones of the Lombardy, is a difficult task if not impossible at all. Certainly they are very ancient and often date back to before Christ. Sometimes they are just the result of syncretism between paganism and Christianity. The most striking case are the witches, widespread in Lombardy, which often have a distinctive feature: they are the priestesses of the Mother Earth, a goddes of pagan origin that the Church -for convenience- used to identify with Satan. The topic is very broad and would need to be explored more specifically: here, it would be enough to note that between the 16th and 17th century the Inquisition spotted several dozen of witches -condemning them to the stake- just in Lombardy, some of them in Milan.

The lombard Alps abound of very special characters, all infamous and all with nocturnal habits, of course. The Tettavach is a strange chimera reptile, a long, thick black snake that can steal the milk of the cows and even introduce itself into cradles of newborns with the same purpose .

2 – The “Tatzelwurm”, figure from 1841 calendar “Alpenrosen”.

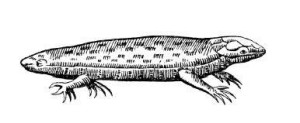

3 – An illlustration of the four-legged “Tatzelwurm” by Ulisse Aldrovandi, naturalist (1522 – 1605).

Its counterpart is the the Tatzelwurm, a big lizard with two or four legs, stubby tail and the same eating habits of the former. Some say that it really exists and in 1934 a certain Balkin claimed that he had taken a photo – that definitely looks fake. The Cavra Besula is rather an enormous goat with flaming eyes that introduces itself with a terrifying yell, and uses to eat those sheperds who have moved away from the bivouac. Every year in Val Camonica it is traditional to celebrate the catching of the Badalisc, that is a beast covered in goatskin, having a huge head, a large mouth and inevitable flaming eyes. The name, badalisc, clearly recall the basilisk, as proof of the ancient origins of this myth. Once again in Val Camonica, but also in the Bergamo valleys and in Valtellina, one can run into the Confinati (pents) who are the souls of those who have died dissatisfied. They were sent into exile in the inhospitable side valleys as a result of an exorcism, so as not to endanger the living ones.

4 – The “Gatto Mammone”, artist illustration.

The Gigat is a creature that is traditional of Sondrio: according to some, it would be a big goat, while others say that it is rather a tremendous huge cat. In this latter case, the gigat would be an analog of the “Gatto Mammone”, another magical beast of proven evil nature. It uses to inhabit the dark alleys and pounce on people and animals to eat them, causing horrific mutilation. Similar to Gigat, but smaller, is the Gata Carogna (dialect for “bastad cat”,[1] widespread in the provinces of Bergamo and Cremona. This is just a big cat with shaggy and tawny fur, that attacks children to steal their souls. Likely, however, the origin of these myths comes from attacks by lynxes or wild cats, so please stay positive about your children. Eastern Lombardy is instead the traditional home of Squasc, a small, hairy, reddish being that looks like a squirrel without tail, with anthropomorphic face. It is a creature less fearful of the previous because it’s not entirely bad: half boogeyman, because it scares the children, the other half is sprite, due to his pranks especially devoted to nice girls.

5 – The “Tarantasio” dragon.

In the province of Lodi you can find two myths for the price of one: a dragon, that scared the pople that lived on the banks of a lake that no longer exists. It was the Tarantasio, that haunted the rivers of the lake Gerundo. It used to eat children and had a pestilential breath with which tainted the air and caused the terrible yellow fever. It also had a questionable habit to smash and sink boats. Its ending is somehow related to the disappearance of the lake: according to some, the killing of the dragon and drainage of the lake are attributable to Saint Cristopher, others say that was due to Frederick I (aka “Barbarossa” or “Red Beard”) or rather to forefather of the House of Visconti, whic has since been carrying the dragon (known as “biscione”) as charge on the coat of arms. Other that a village called “Taranta” (in the surroundings of Cassano d’Adda) named after the dragon, the only thing we know for sure is that the sculptor Luigi Broggini (1908-1983) was inspired exactly to the Tarantasio when conceived the six-legged dog wich then became the very famous logo of ENI national oil and gas company. Also the logos of the Mediaset mass media company, the largest commercial broadcaster in Italy headquartered near Milan, refers to a dragon or rather a big snake. The heraldic figure of the “biscione”, that appears in the coat of arms of the Municipality of Milan and of House of Visconti, could originates both from the basilisk[2] or the “tarantasio”.[3][4]

6 – The coat of arms of the House of Visconti on the bell tower of the church of “San Gottardo in Corte” in Milan, originally built as ducal chapel (1330-1336): the heraldic beast known as “Biscione” could originates both from the basilisk or the “tarantasio” (foto: © Giovanni Dall’Orto).

The wolf need a separate discussion: an absolutelhy real animal, yet turned into a myth because of the terror it could rais in the begone ages to the extent that it triggered and fuelled legends and superstition. In 15th century, the people of Como believed the wolf had a natural inclination towards eating humans. During the 17th century in the area between Varese, Bergamo and Brescia several dozens of wolf attacks resulted in human victims, to the extent that in Milan was organized an army of 500 men armed with schytes, pitchforks and muskets for catching the beast.

7 – The classical appearance of the “Harlequin” character in 17th century (Sands, 1860).

No wonder, then, that in the traditions the wolf is synonymous with fierceness, or even embody something evil like black cats and dogs. From here it was a short step to believing that some men might turn into werewolves and devour children. Even Pietro Pomponazzi (1462-1525), a philosopher from Mantua, in its treatise De Incantationibusargued that human passions could alter physical appearence, thus giving a pseudo-scientific endorsement to popular beliefs regarding lycanthropy. It is quite obvious that the unfortunates believed to be werewolves were sent to the stake along with the witches.

Finally, is worth mentioning an absolutely unsuspected devil: Harlequin, a famous masked character of the Italian popular comedy of the sixteenth through the eighteenth century. Sure enough, there is a very complex legacy behind the popular stock character. His birthplace is undoubtely Bergamo, but his name seems to come from the French devil Harlequin (aka Herlequin or Hellequin), even managing his own team of demon. Others say that “Harlequin” comes from “Erlenkönig”, a goblin of the Scandinavian mythology. In any case, Harlequin is closely related to demonic aspects easily traceable – once again – to ancient cults.

Notes

- [1]“carogna”, spelt exactly the same in Italian, literally means “carcass”, but is often used as a figurative for “lowlife”, “bastard”.)↩

- [2]L’araldica della Regione Lombardia, (op. cit.)↩

- [3]Racconti del Gerundo (op. cit.)↩

- [4]Fayer-Signorelli (op. cit.)↩

Bibliography and sources

- Araldica della Regione Lombardia Milano: Istituto Regionale di Ricerca della Lombardia, 2007. E-book.

- C. Fayer, M. Signorelli, “Racconti del Gerundo: aspetti di un territorio” Milano: SIED, 2001

- Bottani, Tarcisio, Wanda Taufer. “Dannati impenitenti e anime confinate.” Storie e leggende della bergamasca. Clusone: Ferrari Grafiche, 2001.

- Corbella, Roberto Creature del mistero. Fate, folletti e fantasmi

Varese: Macchione, 2004.

- Facchetti, Giulio, M e Federico Crimi. Il gande libro dei misteri della Lombardia, risolti ed irrisolti Roma: Newton Compton, 2011.

- Marelli, Roberto. Bel paese è Lombardia Lainate: A.CAR., 2012 .

- Castiglioni, Giorgio. Studi della Biblioteca Comunale di Moltrasio. Moltrasio: Library of Moltrasio, 2002.

- Castiglioni, Giorgio. “Un misterioso lucertolone.” Mah! Sett. 2005: n.1 Bibliotopia. Web.

- Cominelli, C., S. Lentini, and P.P. Merlin. Tradizioni popolari e istoriazioni rupestri: una prospettiva etno-archeologica. CRAAC. Centro Ricerche Antropologiche Alpi Centrali, n.d. Web. 20 June 2013.

- Tansini, Stefano. “L’incredibile creatura chiamata Bargniff.” Fombio – Notizie dal Basso Lodigiano. n.d. Web.

- “La cavra besula.” Turismo Presolana. n.d. Web.

- “Il Caurabèsul.” Paesi di Valtellina e Valchiavenna. n.d. Web.

- “Festa del Badalisc ad Andrista (località di Cevo).” Atlante Demologico Lombardo. Fondazione Civiltà Bresciana, n.d. Web.

- “Anime confinate in Valle Stabina.” Storie e poesie bergamasche in italiano e in dialetto. n.d. Web.

- Torno, Armando. “Streghe, roghi e magie: quando i lupi mangiavano i bambini.” Corriere della Sera [Milano] 2 Nov. 2008: 12.

- “Leggende lombardia.” Il Libro delle Ombre. n.d. Web. 20-06-2013

Image credits

- © Paolo Ardiani, medieval bridge Val Brembana, Fotolia.com (#52939581)

- dal calendario Alpenrosen, 1841 [PD] Commons

- Ulisse Aldrovandi (naturalist, 1522 – 1605), [PD] Commons

- Jonnyrotten, 2009 [PD] Commons

- Ulisse Aldrovandi (naturalist, 1522 – 1605), [PD] Commons

- © Giovanni Dall’Orto, 2008, Commons

- from Sands, Maurice Masques et bouffons (Comedie Italienne). Paris: Michel Levy Freres, 1860 [PD] Commons.

Originally published in Italian 28th Jun, 2013. English translation by: Silvio Dell’Acqua.